|

Thank you for visiting.

Click here for the Japanese(日本語) version

My name is Kitao Nakamura, the developer of the PC Engine emulator

"Ootake."

This article will inevitably end up praising Ootake a

bit,

but it's not driven by some shallow "look how amazing my

implementation is" kind of motive

(though I certainly don't mind if

people appreciate it).

If someone wants to enjoy PC Engine titles

today but can't play them on original hardware,

I genuinely believe

that Ootake offers the closest experience

without compromising

the quality of the games.

I've always been

concerned that playing in a low-accuracy environment can diminish

the strengths of these works.

By writing about the inner workings

of Ootake like this, I hope it will help raise

the overall level of

the emulator scene, even if only a little.

I plan to cover

several topics over the coming installments.

This time, the focus is

on color reproduction.

In developing Ootake, I connected real PC Engine hardware to

both CRT televisions

and modern LCD monitors, studied the

output until I practically wore holes in my eyes,

and implemented

the color reproduction based on

what I understood to be the

original developers' intentions.

As far as I know,

Ootake is the only emulator whose default settings are based

directly on

how colors actually appear through the real hardware's

composite and RF output.

Including commercial re-release hardware and software, most

other PC Engine emulators are

built on the assumption of displaying

output from a PC Engine modified for RGB.

As a result,

their colors differ significantly from what you see through

the real

hardware's composite or RF output.

So, which one represents the

original, intended look?

RGB Mods and Expansion-Bus RGB Output Use Uncorrected Signals

By modifying a real PC Engine to tap the RGB signals

directly from its internal chips and adding an RGB output port,

you can connect it to any display that accepts RGB input.

However, when you use this kind of modification, the

resulting image ends up showing colors that differ quite a lot

from the PC Engine's original appearance.

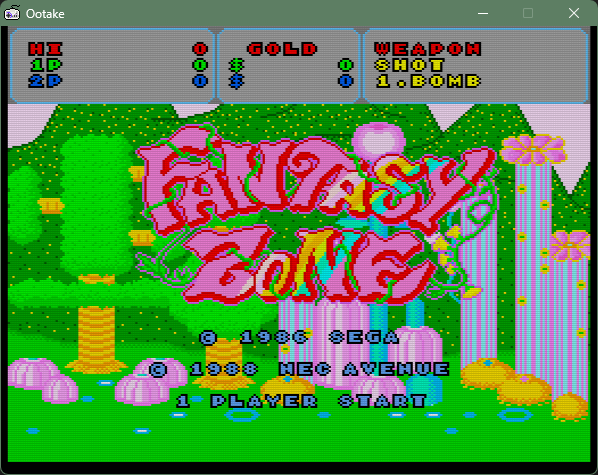

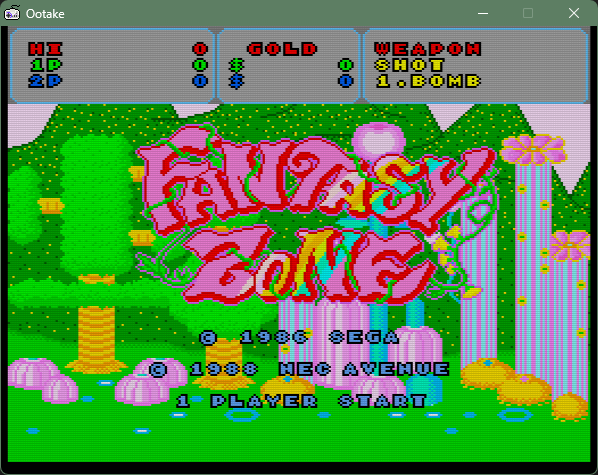

↓Ootake's default display. It closely matches the

familiar look of real hardware's

video output.

— There were also many televisions of that era that had

somewhat paler

colors than this, due to

considerable unit‑to‑unit variation.

Note: Colors may appear different in some PC browsers.

For accurate color reproduction, please save the image

and view it in Paint.

Ootake setting: Default

Source: "Fantasy Zone" (© SEGA, © NEC

AVENUE)

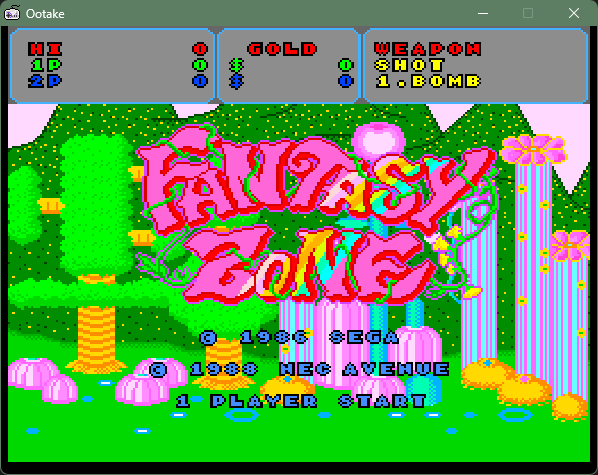

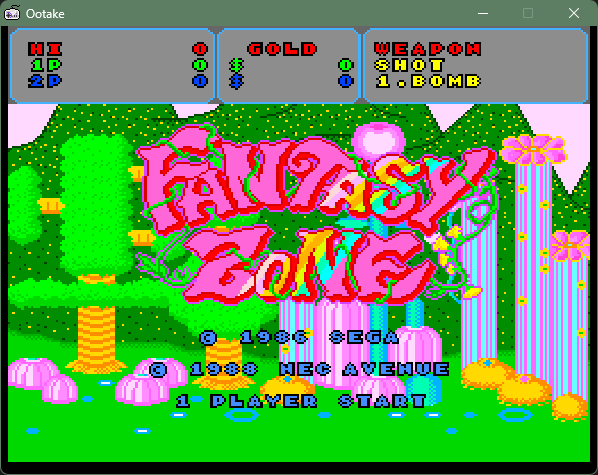

↓Displayed with Ootake set to approximate a modified RGB‑output

unit.

The red tones become stronger, giving the

image a more primary‑color look.

Because the

contrast is too high, the overall color balance appears overly

harsh and garish.

In the PCE

version of "Fantasy Zone", this difference becomes critical.

Note: Colors may appear different in some PC browsers.

For accurate color reproduction, please save the image

and view it in Paint.

Ootake setting:

Gamma 0.94 , Brightness +30 ,

Non-Scanlined

Source: "Fantasy Zone" (© SEGA, © NEC

AVENUE)

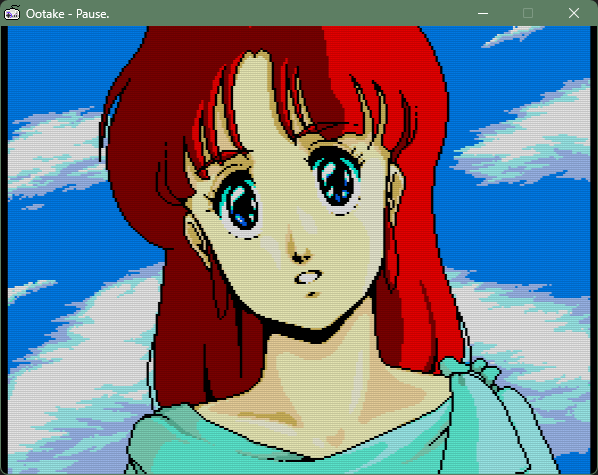

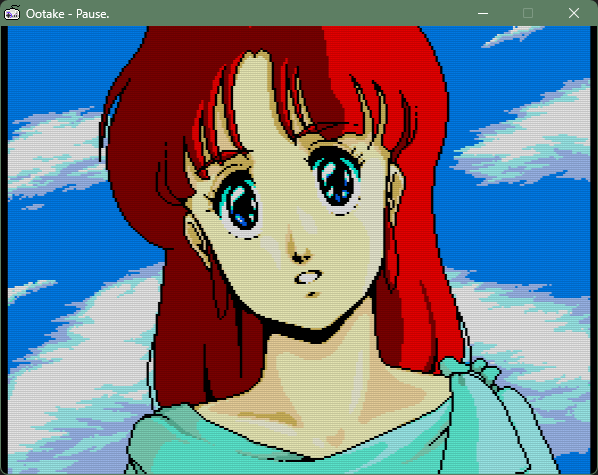

↓Ootake’s default display. It has a

familiar vibe, close to the video output of

real

hardware.

Lilia in the Ys II opening. Even the

“shadowed skin tones” in the darker areas

still

remain recognizably skin-colored.

Note: Colors may appear different in

some PC browsers.

For accurate color reproduction, please save the image

and view it in Paint.

Ootake setting: Default

Source: "Ys I・II " (© Falcom © Konami Digital

Entertainment)

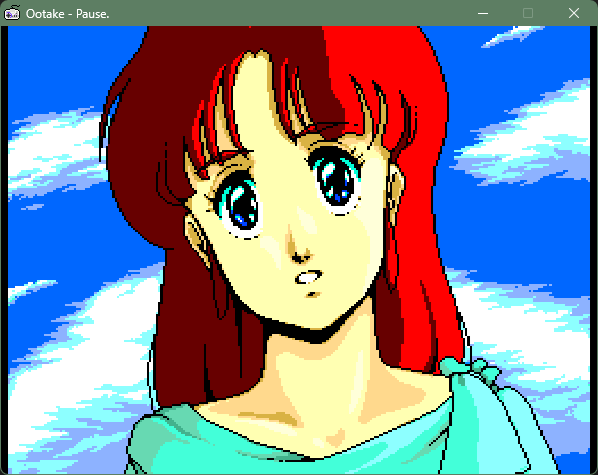

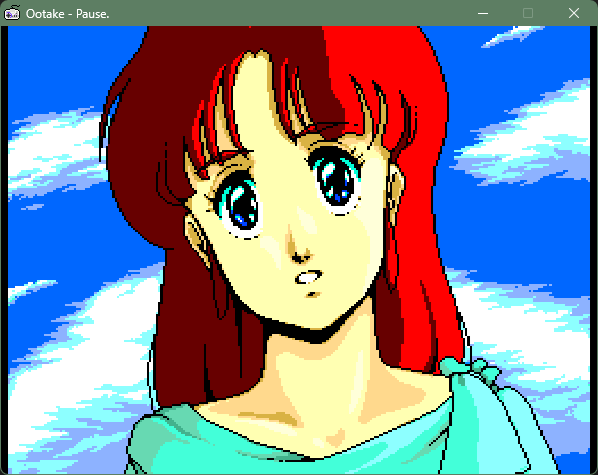

↓Ootake set to a configuration similar to many other emulators.

Reds appear more intense.

Unlike real hardware,

the shadowed areas sink too dark, causing skin tones

and hair colors to look dull.

Note: Colors may appear different in

some PC browsers.

For accurate color reproduction, please save the image

and view it in Paint.

Ootake setting: Gamma 0.94 ,

Brightness +30 , Non-Scanlined

Source: "Ys I・II " (© Falcom © Konami Digital

Entertainment)

Because RGB output looks sharp and clean, many people have

assumed it to be "correct" without noticing the color

differences.

The same applies to modifications

that extract RGB signals from the rear expansion bus; without

proper adjustment, the resulting colors will differ from the PC

Engine's original appearance

On real PC Engine hardware, the video is originally displayed

through the following process:

Internal RGB signals → Converted into

TV‑compatible video signals (colors are altered in this step) →

Composite/RF output

However, on an RGB‑modded unit:

Internal RGB signals → Output directly

as RGB with their original, unadjusted color values

Because the RGB output bypasses the

color‑adjustment stage, what you see is the raw RGB

signal rather than the PC Engine's intended color

appearance.

The first PC Engine emulator ever

created, "VPCE" — developed by a programmer in Germany — was

implemented based on the color output of an RGB‑modded PC

Engine.

For roughly sixteen years after Ootake's release,

nearly all subsequent emulators and commercial re‑release

hardware also followed this RGB‑modded color baseline.

About sixteen years after Ootake introduced a color reproduction

closer to real hardware, users of the FPGA‑based MiSTer platform

began noticing the differences from actual PC Engine units and

implemented settings that move the colors closer to

real‑hardware accuracy.

In the next chapter, we will

explore why, for so many years, most emulators continued to

use colors that differed from those of real Japanese PC

Engine hardware.

|

Why So Many Emulators Continued Using Colors That Differ from

Real

Japanese Hardware

Why were the first PC Engine emulators — "VPCE" and, a few

months later, "Magic Engine" — implemented with colors that

differed from real Japanese hardware?

The reason is that

in Europe, NEC's officially released PC Engine models were

extremely rare.

Most users imported Japanese PC Engine

units and purchased them already modified with RGB output

ports, making RGB‑modded consoles the de facto standard in that

region.

The creator of "VPCE" was from Germany, and

the creator of "Magic Engine" was from France. It is highly

likely that the hardware they owned were Japanese PC Engine

units that had already been modified with RGB output.

The

reason is that NEC's officially released European PC Engine

models operated at 50Hz, which caused Japanese games to run in

slow motion.

Both of these emulators were designed to

run at 60Hz — the same refresh rate as Japanese PC Engine

hardware — rather than 50Hz.

In France in particular,

consumer televisions commonly included RGB (SCART) inputs as a

standard feature. Because of this, Japanese PC Engine units

that had already been modified for RGB output were routinely

sold in many game shops.

It is also plausible that

the German creator of "VPCE" took advantage of this French

market and imported not only the console but even a compatible

television.

Since these RGB‑modified PC Engine units were

effectively the mainstream option in Europe, it was only natural

that early emulators ended up reproducing colors that

differed from those of real Japanese hardware, which relied on

composite or RF output.

Several factors likely contributed to why this situation

persisted for so many years, even among Japanese emulators,

including commercial ones:

- The developers' own PC

Engine units may have been RGB‑modified consoles.

- Many

developers never directly compared the colors of real hardware

with those of their emulators.

- Because most emulators

shared the same RGB‑based color tone, it was widely assumed to

be correct without further verification.

- Even with

inaccurate colors, games remained fully playable; darker color

reproduction rarely caused issues severe enough to hinder

gameplay.

As a result, many games end up being played

with colors quite different from what their original designers

intended, preventing the true appeal of their artwork from

being fully appreciated.

There are, in fact,

several PC Engine titles that have been unfairly judged due to

this lack of accurate color reproduction. In the next

chapter, we will take a closer look at these misunderstandings

and explain them in detail.

|

Fantasy Zone's Beautiful Real‑Hardware Colors, and

Gradius's

Not‑So‑Dark Appearance

As shown in the images

from the first chapter, the PC Engine version of

Fantasy Zone can look noticeably harsher and more toxic in color

when played with the default settings of emulators other than

Ootake.

Because of this, it is not uncommon to see

reviews claiming that the PC Engine version has "bad colors."

One review written in the early 2000s had a particularly

strong influence. For a time, people hostile toward the PC

Engine would repeatedly link to that article on a major Japanese

anonymous online forum and use it to disparage the PCE version

of Fantasy Zone.

The problem was that the review relied

on emulator screenshots that did not reproduce real‑hardware

colors, declaring that "the colors are wrong," and then

listened to heavily degraded emulator audio and concluded that

"the sound is terrible."

In reality, both

judgments were based on inaccurate reproduction rather than the

actual capabilities of the hardware.

Looking back at

reviews and user impressions from that era, there were no

complaints about the colors at all. The screenshots printed

in manuals and magazines consistently showed a clean and

attractive-looking Fantasy Zone.

As for the sound, it is

true that people occasionally mentioned being disappointed that

the whistle in Stage 1 was missing.

However, many players

also appreciated the strengths of the other stage themes, and at

the time there were no widespread criticisms or reviews harshly

attacking the audio.

It is unfortunate that, years later,

some people began repeating negative claims without verifying

the facts, simply echoing what they saw online.

This

kind of uncritical bandwagon criticism can easily lead to unfair

evaluations taking root.

On the other hand, here is a review from 2020 of the PC

Engine mini, published by GAME Watch.

"PC Engine mini: Full Title Review –

Fantasy Zone" (GAME Watch)

In

it, the reviewer writes:

- "The colors are slightly

different, but the screen layout is almost identical to the

arcade version."

- "It doesn't come across in screenshots,

but the BGM feels a bit underwhelming."

While reviewing

Fantasy Zone as it appears on the PC Engine mini, the author

also reflects on the original PCE version:

"At the

very least, to me at the time, the image on my home TV looked

almost the same as the arcade version."

The

difference lies only in the color reproduction of the PC Engine

mini, not in the reviewer's original memory.

Their

impression from back then was not mistaken at all.

As for the sound, the PC Engine mini unfortunately has

several inaccuracies in its audio reproduction—for example, the

noise‑based drums can be overly sharp and distracting.

In

Fantasy Zone, these issues stand out even more, to the point

that the mini fails to convey the simple, charming sound of the

original PCE version.

To help clear up these

misunderstandings, I hope to share audio samples from Ootake or

real hardware on X when the opportunity arises.

Other titles that feel visually off unless played on real

hardware or Ootake include games like "Gradius" and "Dungeon

Explorer."

On most general-purpose emulators, these games

appear extremely dark, with colors that look dull and washed

out.

↓Ootake default display. The overall look is close to the

familiar video output

of real hardware.

Although darker than many other games, it is not excessively

dark and

actually creates a nice atmosphere.

Note: Colors may appear different in some PC browsers.

For accurate color reproduction, please save the image

and view it in Paint.

Ootake setting: Default

Source: "Gradius" (© Konami

Digital Entertainment)

↓Ootake set to a configuration similar to many other

emulators.

The overall image looks darker.

The player ship's gray, as well as ground enemies and items, all

appear

somewhat dull.

Note: Colors may appear different in some PC

browsers.

For accurate color reproduction, please save the image

and view it in Paint.

Ootake setting:

Gamma 0.94 , Brightness +30 ,

Non-Scanlined

Source:

"Gradius" (© Konami Digital

Entertainment)

In many other games as well — such as the Ys, Tengai Makyo, Valis,

and Cosmic Fantasy series — comparing elements like skin tones

and the smoothness of sky gradients reveals color differences

that are too significant to ignore.

In the next chapter, I will explain how Ootake

reproduces the colors of the Japanese PC Engine — the colors

originally intended by the designers.

|

How to Reproduce the Colors of the Japanese PC Engine

— the

Colors Intended by Its Original Designers

So then, how can we bring the colors closer to those of real

hardware?

Around five years ago, an overseas enthusiast

succeeded in extracting and digitizing the correction values

used when converting the PC Engine's internal RGB signals into

composite or RF video output.

Displaying an emulator's

screen using raw RGB data alone is less accurate than applying

these correction values.

With the correction applied, the

resulting image indeed becomes much closer to the look of a real

Japanese PC Engine — as well as to Ootake's color reproduction.

However, even with these correction values applied,

the result still differs somewhat from "the final colors."

This is because, on real hardware, the correction values are

followed by an additional conversion into analog video signals.

After that, the signal passes through the television's own

brightness‑adjustment circuitry before finally appearing on the

screen.

In contrast, Ootake has focused on

reproducing "the final colors" from the very beginning

— ever since its earliest version released twenty years ago.

More concretely, Ootake is built on the following

principles:

- Never place colors arbitrarily;

always preserve the overall balance.

- Ensure that

color adjustments do not break games that are

particularly sensitive to color tone, such as "Fantasy

Zone", "Gradius", or "Dungeon Explorer".

- Compare

the output against real hardware as closely as

possible, adjusting until the overall atmosphere feels right.

- Televisions of that era had lower contrast than modern

digital displays, partly to prevent dark scenes in movies or

video content from becoming completely black.

As a result,

darker areas tended to appear somewhat brighter compared

to today's TVs.

- Because early televisions varied

widely in their factory calibration, with significant

unit‑to‑unit differences in color tone, it is impossible to

define a single "correct" color.

This is something that must

be kept firmly in mind from the start.

Based on these principles, the actual implementation

followed the guidelines below:

- Use sRGB as the

foundation for the overall color balance.

- Adjust

the gamma curve to prevent dark areas from sinking too deeply,

aiming for a look that is both close to real hardware and easy

to view.

- Do not rely on a single hardware‑and‑TV

combination; instead, verify the results across multiple real

setups. * I also frequently visited retro game shops to

study the colors on their in‑store demo TVs.

Through this kind of repeated trial and error, I gradually

refined the implementation.

The default

settings used by most players are chosen with great

care, so that the intentions of the original creators are

faithfully conveyed to the player.

Because televisions of

that era varied so widely from unit to unit, Ootake also allows

users to make their own adjustments — within a range that does

not break the overall color balance — using the "Gamma" and

"Brightness" menus.

|

To Preserve the Appeal of These Classics for

Future Generations

If the person who wrote that heavily misunderstood review of the

PCE version of "Fantasy Zone" had been using an emulator with

accurate color and audio reproduction, the article likely would

never have turned out the way it did.

When PC Engine

emulators first appeared, simply seeing those nostalgic games

running on a PC screen was enough to excite and move me.

However, as emulators became more widespread, I realized that

low‑accuracy reproduction carried the risk of causing

these games to be unfairly judged.

That

realization became the single biggest reason I decided to

release Ootake.

I wanted to make it available as an emulator

that could faithfully convey the strengths of the original

works.

One thing I personally try to be very careful

about is that digital measurements, if taken in the wrong way,

can easily lead to incorrect implementations.

For that

reason, I believe the best approach is to verify reality

through analog observation and use digital data

only as supporting evidence.

Since the

ultimate goal is for the emulator's output to match that of real

hardware, the most reliable method is simply to place

the two screens side by side and compare them directly.

If any differences appear, I revisit the data — and then confirm

the results again through analog observation.

Without this

cycle of repetition, a highly accurate emulator cannot be

achieved.

It isn't an easy task, but with the hope that

these classics will continue to be enjoyed in their true form, I

will keep refining Ootake.

|

2026.2.6 Written by Kitao Nakamura.

"Ootake" Homepage へ 戻る

|

Twitter(X)始めました

Twitter(X)始めました